On April 25, 2016, the Cryptome foundation disclosed that a large zip archive containing what seemed to be private data from hundreds of thousands of customers of the Qatar National Bank (QNB, the largest bank in the Arab Gulf in terms of assets) had been posted online.

The archive

The archive (510MB compressed, 1.4GB uncompressed) contained about 15K files in many directories. The most obviously significant were (1) a set of database tables, and (2) a directory named "Folders."

The directory named "Folders" is a set of small dossiers of about 100 "notable" people in Qatar. It includes several sub-folders named "Al Jazeera" (the name of the Qatar-based news network), "Al Thani" (the name of the ruling family), "Police, security" and so on. Inside each folder, there is one or more files containing a mixture of data extracted from the QNB database (such as account number, passport number, and so on), and information from other sources, that varies from links to online profiles to a photo of the person, usernames and passwords. I say "notable" in quotes because the classification of people into folders here is a little bit dubious, for instance with some people named as spies when they are unlikely to be so.

The database tables contain profile information of about 300K-400K customers. This includes name, nationality, passport number, national ID number in Qatar, e-mail address, and physical address. It also includes card numbers, expiration dates, and account numbers for about 800K-900K debit and credit cards. There is some duplicate information between a set of main files and a set of back-ups, so the number varies depending on which files you look at.

My involvement

I worked in Qatar from mid-2012 to mid-2015 as a scientist in a national research institute. From my time in Qatar I knew that QNB is the first choice for many foreign workers, so the data leak had probably affected many of my colleagues who still work in Qatar.

After downloading the archive I did a quick search for e-mail addresses in my former institute, I found 4 people I knew, including their full names, which was a strong signal that the archive was authentic. Additionally, there were things that you only see in Qatar (such as writing "QATAR FOUNDASHON" instead of "QATAR FOUNDATION"). I alerted my colleagues, but didn't want to look more into the archive; I was not interested in learning anything private from them, and given I did not find my own e-mail address, I assumed this was old data from before I went to Qatar.

However, hours later and after being alerted by a friend, I did find my account in the archive. My e-mail ID was not included in the main files, but in one of the backups, and my national ID number in Qatar was in multiple places.

I looked more carefully in the archive and found the names of people I knew, but not their e-mail addresses. Then, I decided to create a tool to let people search for themselves if they were present in the archive or not.

The "QNB Verifier"

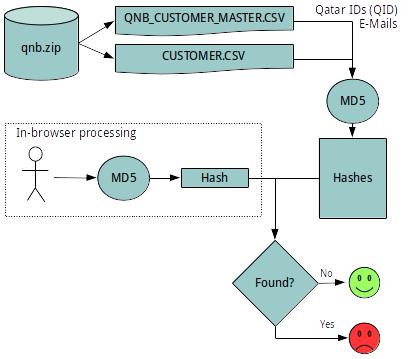

The tool I set up on April 26th was very simple. First, I hashed all the e-mails and Qatar national ID numbers I could found and uploaded the hashed identifiers to my web server. Second, I wrote a small Python script (my first program in Python) to receive a hashed user input and compare it against the stored hashes. Third, I used an Javascript implementation of MD5 to hash the input in the browser of the user.

The tool I set up on April 26th was very simple. First, I hashed all the e-mails and Qatar national ID numbers I could found and uploaded the hashed identifiers to my web server. Second, I wrote a small Python script (my first program in Python) to receive a hashed user input and compare it against the stored hashes. Third, I used an Javascript implementation of MD5 to hash the input in the browser of the user.

I set-up a page to give access to this tool to users, and warned them that their hashed input could be observed while in transit, but indicated that no plain-text personal data would leave their browsers. I also made it clear I was not hosting the leaked files. I kept no logs of the user input but my service providers has statistics of how many people accessed the endpoint of the service. About 10,000 did so during the 5 days or so that the service was active.

In the meantime, QNB continued calling this a "social media speculation," a line they maintained for several days.

The denial-of-service attack

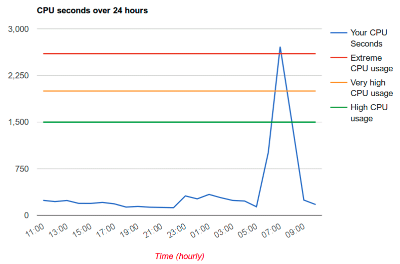

From April 27th onwards I started to get thousands of requests per second from a few IP addresses. This increased substantially the CPU usage of my account. My hosting provider froze all my websites (i.e. started serving static versions of them) except for this verification service (!) and warned me that if this high CPU usage continued they will suspend my account.

From April 27th onwards I started to get thousands of requests per second from a few IP addresses. This increased substantially the CPU usage of my account. My hosting provider froze all my websites (i.e. started serving static versions of them) except for this verification service (!) and warned me that if this high CPU usage continued they will suspend my account.

I added the IP addresses of the attacker to a blacklist but s/he kept on changing them. I spent hours playing whack-a-mole but fortunately for me the attack was not very sophisticated, and eventually my attacker gave up and stopped changing IP addresses. That brought my traffic down to normality and my websites were unfrozen.

The legal threats

On April 30th the service was featured in Doha News. Doha News is an independent online news service that operates from Doha. They knew me from my time in Qatar and had covered some of the work on predictive news analytics that my team did for Al Jazeera. They linked to the verification service and interviewed me over Twitter to know about my reasons and how this worked. The International Business Times also followed up on this story.

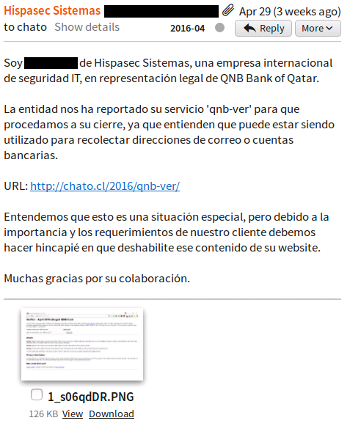

On the same day, I received an e-mail from Hispasec, a Spanish IT security firm. In their e-mail, they wrote in Spanish:

On the same day, I received an e-mail from Hispasec, a Spanish IT security firm. In their e-mail, they wrote in Spanish:

I am .... from Hispasec Systems, an international IT security company, in legal representation of QNB Bank from Qatar.

The entity had reported your 'qnb-ver' service for us to proceed to shut it down, because they understand it can be being utilized to collect e-mail addresses or bank account numbers:

URL: http://chato.cl/2016/qnb-ver/

We understand this is a special situation, but due to its importance and the requirements of our customer, we must emphasize that you must disable this content from your website.

Many thanks for your collaboration.

I responded a couple of days later and had some exchanges with them. I basically stated that I was not hosting the leaked files and that I was not collecting any data. They reinstated their request and warned me about the importance of promptly removing my service to "avoid to face any legal action concerning the spreading of the public damage and defamation." I have to say I never felt this was something to be concerned about; in Spain you are fairly safe unless you speak against the king.

Censorship

The Internet has always been heavily censored in Qatar, and many different content categories are not accessible from the country. Censorship is, however, quite easy to circumvent with VPNs, and many people use them.

The Internet has always been heavily censored in Qatar, and many different content categories are not accessible from the country. Censorship is, however, quite easy to circumvent with VPNs, and many people use them.

On 2014 or 2015 they set-up a censorship page, that you can see in censor.qa that shows a cartoon and explains that you have accessed a page that contains prohibited materials. This makes censorship more "friendly," I guess.

My page was added to Qatar's blacklist on May 1st, 2016. I set-up an alternative, https-based access on the same day and publicized it, people continued being able to access the https-based service.

Incidentally, on May 1st, 2016, Qatar National Bank issued a statement indicating that the leak had only affected a "a portion of Qatar-based QNB customers." I would say that "portion" is very high, close to 100%. I did not hear about a single QNB customer that used my service and did not find his/her national ID or e-mail in the leaked files.

Downfall

On May 2nd QNB contacted my hosting provider to report a "phishing" attempt from my account. Phishing is when scammers send people e-mails asking them to follow a link that looks like a bank's homepage (or other institution), so that the victims enter their credentials in the fake site, and the scammers can steal them.

In response to the phishing complaint, and without any examination, my hosting provider proceeded to close all the websites hosted in my account, including my personal site, my research site, the website of my upcoming book, the personal website of my wife, an environmental portal that she maintains, and others.

I replied to the report with a detailed explanation that no personal data was being hosted, and no data was being stored, moreover that the service was designed to make this impossible by hashing the personal data on the users' browser. I received an automated response that pointed out the offending files were still there. Basically, a human would not look at the ban until the files were removed.

So, I had to shut down the service, and it took me about one day to get my hosting provider to bring the websites back into operation. I did not want to fight this. Their business is to have customers that don't require any attention, and if you use too much time from the support desk, they can easily revoke your contract and send you with a nice backup in search for another hosting. In my past experience that is 2-3 days of work that I don't have.

What did I learn?

In my opinion, data leaks should be regulated similarly to work place accidents. Companies should have to file an official report indicating what happened and who was affected. Most importantly, customers must be told the truth, but they get nothing, or lies, or partial truths that are not helpful. This is not a problem only in Qatar (many others have done exactly the same), but is definitively made worse by Qatar censorship and heavy-handedness against any "troublemakers."

I learned a couple of things. First, the public is very weak in these situations. You cannot know if your data has been leaked or not, Downloading the archives and verifying yourself takes some technical knowledge that, while superficial, is beyond reach for many people. The are services that can help you, such as Have I Been Pwned?, but they use only e-mail IDs.

There are way too many choke points, from legal systems, to censorship systems, to hosting providers, that can be used to silence anyone. Also, if I had been in Qatar I would have risked jail time followed by deportation, and most likely I wouldn't have done this under those circumstances.

Second, we are also quite strong, for many reasons. The leaked archive is out there and is not going to disappear: you don't get the genie back in the bottle on the internet. That is good because people can still verify if their information was stolen, but bad because the archive contains personal data and hence the potential for abuse is huge.

We are also powerful because we are many and we can move fast, way faster than what many corporations and governments can.

What else did I learn? If I had to do the same thing again, most likely I would find a secondary hosting provider and do it there; the price of getting your main hosting account attacked is too high, and while I was expecting QNB would go to my hosting provider, I thought they would at least look at the complaint to examine its merits. There are many hosting providers that are better suited for this than the standard ones. I would also set-up this under https from the beginning to make it more resilient and secure.

Everything else, I would do the same. It was the right thing to do, and I'm glad I was able to help.